By Eric Madis[1]

Taekwondo (t’aegwondo, kicking and punching way/art) is a Korean martial art and combative sport distinguished by kicks, hand strikes, and arm blocks. Its sanctioned history claims that taekwondo is 2,000 years old, that it is descended from ancient hwarang warriors, and that it has been significantly influenced by a traditional Korean kicking game called taekyon. However, the documented history of taekwondo is quite different. By focusing solely on what can be documented, the following essay links the origins of taekwondo to 20th century Shotokan, Shudokan, and Shito-ryu karate, and shows how the revised history was developed to support South Korean nationalism.

Imperial Japan began its domination of Korea and Manchuria in the 1890s. Both Russia and China unsuccessfully attempted to control Japan’s expansion into the region. The Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) resulted in the Treaty of Portsmouth, which placed Korea under the “guidance, protection and control” of Japan (Harrison, 1910: 499). Finally, on August 29, 1910, King Sunjong (ruled 1907-1910) of the Yi Dynasty (1389-1910) was forced to abdicate his throne, thereby completing Japan’s annexation of Korea (Lee and Wagner, 1984: 313).

Japan’s colonization of Korea lasted from 1910 to 1945. Japanese policy towards the Korean populace was guided by factors such as Japan’s economy, Japan’s international situation, and the policies of individual governors-general (Lee and Wagner, 1984: 346). Therefore, treatment of Koreans varied from paternalism to severe repression (Breen, 1998: 103-115; Korean Embassy, 2000). At all times, however, Koreans were treated as second-class citizens.

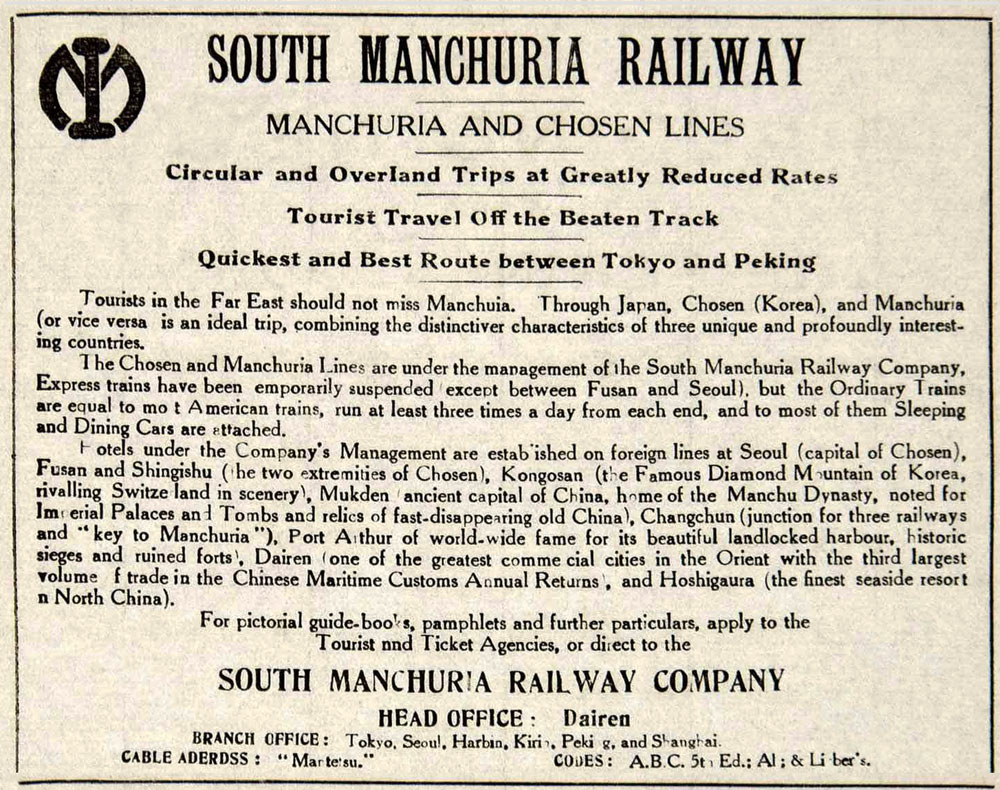

Under Japanese rule, the Koreans were compelled to participate in Japanese imperialism (Breen, 1998: 105). Nearly one million Koreans emigrated to Manchuria (Schumpeter, 1940: 70). Some worked in agriculture while others worked in mining, petroleum, and heavy industry. The primary employer was the South Manchurian Railway (南鐵), a huge, multifaceted Japanese company, similar to the British East India Company, which spearheaded Japanese expansion into Manchuria and northern China (Harries and Harries, 1991). Furthermore, police forces in Manchuria were largely comprised of Koreans (Jones, 1949: 33).

By 1940, another million Koreans resided (sometimes involuntarily) in Japan (Schumpeter, 1940: 70), and during World War II, this number grew to as many as 2.4 million (Chin, 2001: 59). The majority of them worked in factories or coal mines. Many Koreans served in the Japanese military, while others involuntarily served Japanese war efforts as laborers or “comfort women” (Breen, 1998: 113)

Conversely, some affluent Koreans chose to send their children to preparatory high schools and universities in Japan, both for education and to establish the peer relationships necessary for success in Japanese-dominated society (Lee, 2002a).

OKINAWAN KARATE COMES TO JAPAN

After participating in an exhibition of Japanese martial arts in April 1922, Okinawan educator and karate adept Funakoshi Gichin (1868-1957) remained in Tokyo. Later that year, Funakoshi began teaching karate at the Okinawan student dormitory (meisi juku) at Japan University in Tokyo (Funakoshi, 1975: 69-71). Interest in karate grew steadily, allowing Funakoshi to establish a training hall (Japanese, dojo; Korean, dojang) at Keio University in 1924 and another at Tokyo University in 1926. Between 1928 and 1935, Funakoshi established more than 30 dojo, most of which were at educational institutions (Cook, 2001: 76; Funakoshi, 1975: 75).

Growing interest in karate encouraged other Okinawan instructors to move to Japan. Examples include Uechi Kanbun (1877-1948) in 1924, Mabuni Kenwa (1889-1952) in 1928, Miyagi Chojun (1888-1953) in 1928, and Toyama Kanken (1888-1966) in 1930 (McCarthy and McCarthy, 1999: 18, 126). Mabuni established dojo in Osaka, including several at universities. Toyama established the Tokyo Shudokan in 1930 and taught at Nihon University. It was in these Japanese university clubs that some Korean students studied the arts that would become the foundation of future Korean karate styles.

The introduction of karate to Okinawan public schools began in 1901 (Bishop, 1989: 102). The pioneer was Itosu Ankoh (1832-1915). A leader and innovator from the Shorin-ryu (Shaolin school) karate lineage, Itosu not only modernized, but created many of the forms (Japanese: kata; Korean: hyung) that are practiced in karate today. Examples include the pinan (peaceful mind; in Japanese: heian; in Korean: pyongahn) kata, which were a series of five forms designed to advance students from beginning to intermediate level in a class setting (Cook, 2001: 52). Itosu also taught and mentored many of the major figures of modern karate, including Funakoshi, Mabuni, and Toyama. In addition, Itosu embraced the promotion of karate as a means of developing Japanese spirit (yamato damashi), which contributed to karate’s acceptance and popularity in Japan (Bishop, 1989: 103; Cook, 2001: 25)

Yabu Kentsu (1866-1937), who was a student of Matsumura Sokon (1809-1901) and Itosu, also had a profound influence on modern karate training. A former officer in the Japanese army, Yabu introduced many procedures still practiced in karate schools worldwide, including the Korean styles. These innovations included

- Bowing upon entering the training hall

- Lining up students in order of rank

- Seated meditation (a Buddhist practice further developed in Japan as a result of kendo influence)[2]

- Sequenced training (warm-up exercises, basics, forms, sparring)

- Answering the instructor with loud acknowledgment

- Closing class with formalities similar to opening class (Cook, 2001: 26-28, 52-53; Donahue, 1993; Ryozo, 1986)

Most of these procedures already had been implemented in judo and kendo training, and reflect a blending of European militarism and physical culture with Japanese neo-Confucianism, militarism, and physical culture (Abe, Kiyohara, and Nakajima, 1990/2000; Friday, 1994; Guttmann and Thompson, 2001). However, these procedures did not exist in China, or in Okinawan karate before Yabu; neither were they part of taekyon practice in Korea (Pederson, 2001: 604).

Yabu was a primary assistant of Itosu in Okinawa. Thus, his methods were widely adopted by other Okinawan instructors in Japan, including Mabuni, Funakoshi, and Toyama. These training procedures, which were not found in karate books, set the standard for modern Korean karate training and clearly indicate Japanese influence.

The use of belted white cotton martial arts uniforms (Japanese: dogi; Korean: dobak) is relatively recent, having been introduced in Japan during the late 19th century by judo founder Kano Jigoro (Cunningham, 2002; Harrison, 1955/1982: 43-44). Funakoshi modeled the designs of his karate uniforms after Kano’s judo uniforms, and introduced them into his classes around 1924 (Cook, 2001: 62; Guttmann and Thompson, 2001, 147; McCarthy and McCarthy, 2001: 130). Before these uniforms, students practiced in loose-fitting everyday clothes or, in subtropical Okinawa, as little clothing as possible. Anyway, modern taekwondo uniforms are essentially identical to the ones used in karate, providing further evidence of Japanese influence.

THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE MAJOR KOREAN SCHOOLS

Chungdokwan

Lee Won-kuk (born 1907) was possibly the first Korean student to study karate. Lee moved to Tokyo in 1926 to attend high school. He subsequently majored in law at Chuo University. At Chuo, he studied Shotokan karate under Funakoshi Gichin and his son Yoshitaka (Gigo). Since the Chuo University dojo was founded after 1928 but before 1935 (Cook, 2001: 76), this suggests that Lee began studying karate in the early 1930s.

Although Lee has not specified his Shotokan rank, several clues allow an estimation of second or third dan (degree of black belt). Noted Shotokan instructor and historian Kase Taiji states that, in 1944, only three students (Hayashi, Hironishi, and Uemura) held fourth dan rank. Kase remembers only one Korean with second dan rank, who later returned to Korea (Graham Noble, personal communication, July 2000). Subsequently, Lee was the acknowledged senior student of Shotokan in Korea.

After returning to Korea in 1944, Lee received permission to teach karate, first to Japanese nationals and later to a select group of Koreans at the Yungshin School gymnasium in Seoul (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 1, Section 1-1). Lee named his organization the Chungdohwe (Blue Wave Association), which became known as the Chungdokwan in 1951. Lee called his art tangsoodo (China hand way) (Hwang, 1995: 26; Massar and St. Cyrien, 1999). The name was the Korean pronunciation of Funakoshi’s mid-1920s spelling of “karate-do” using the Tang/China prefix.[3]

As Korea’s leading Shotokan-trained instructor, Lee played an important part in Korean karate development from 1944-1947.

In those days, training at the Chungdohwe generally reflected the training Lee received with Funakoshi Gigo. For example, it emphasized strong basics and forms, utilized the striking post (Japanese: makiwara; Korean: tal yul bong), and included one and three-step sparring drills (Cook, 2001: 76-96; Lee, 1997; Massar and St. Cyrien, 1999). As Lee has said

The lessons were popular and many people wanted the training. We had to be careful to recruit and keep only the best, most highly motivated students. The students we kept included some of the prominent figures in modern taekwondo. We worked hard to keep up the quality of instruction and our students, and to promote tangsoodo as a positive influence in Korean society. Our main objective was to instill discipline and honor in young people left without strong moral guidance in those troubled times (Lee, 1997).

In 1947, the head of Korea’s national police, Yun Cae, approached Lee with an offer from the Republic of Korea’s (ROK) President Rhee Syngman (Yi Sung-man). If Lee could convince his entire 5,000-member institute (kwan) to join Rhee’s political party, he would be appointed Minister of Internal Affairs. Lee refused. According to Lee, “I was concerned that the government’s motive for enrolling 5000 martial artists in the president’s party was not to promote justice, so I politely declined the offer” (Lee, 1997).

Immediately, Lee was accused of being pro-Japanese and the leader of an assassin group. This is ironic because, according to the noted Korean scholar Lee Jeong-kyu, “during the 12 years of Syngman Rhee’s administration (1948-1960), 83% of 115 cabinet ministers were Japanese agents or collaborators under Japanese colonial rule” (Lee, 2002a). Soon after, Lee, his wife, and several of his top students were arrested.

After his release in 1950, Lee continued to feel threatened by the political climate, so he relocated to Japan (Lee, 1999; Massar and St. Cyrien, 1999). His absence, combined with Korean War disruption, led to some of his senior students establishing their own institutes. These included Hwang Kee, Moodukkwan; Son Duk-sung, Chungdokwan; Kang Suh-chang; Kukmookwan; Choi Hong-hi, Ohdokwan; Lee Yong-woo, Jungdokwan; and Ko Jae-chun, Chungryongkwan (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 1, Section 1; Lee, 1997; Massar and St. Cyrien, 1999).

Songmookwan

During the late 1930s, while attending a Tokyo university, Ro Byung-jik (dates unknown) received first dan ranking in Shotokan karate from Funakoshi. Ro subsequently returned to Korea. Exactly when is not known, but Lee Won-kuk has stated that he met Ro in 1940 in Tokyo and that Ro worked as a policeman in Seoul during World War II. In any event, on March 11, 1944, Ro opened a dojang in Kaesong (now North Korea), calling it the Songmookwan (Martial Life Institute) (Losik, 1999). Song also means “pine,” and alludes to Ro’s prior Shotokan (Pine Wave Institute) training (Funakoshi, 1975: 84-85; Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 1, Section 5).

Despite his close association with his senior, Lee Won-kuk, Ro called his art kongsoodo, meaning, “empty hand way,” rather than tangsoodo, meaning “China hand way” (Hwang, 1995: 26; Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 1, Section 5). The name preferences are significant, as they reflect changes that occurred in Japan during the years that Lee and Ro studied Shotokan karate.

Owing to Kaesong’s underdevelopment and remoteness, the Songmookwan soon closed. It reopened in 1946 at the Kwandukjung archery school in Kaesong. It is unclear if this newer dojang closed before or after the establishment of the People’s Democratic Republic of Korea on September 9, 1948. However, Ro relocated to Pusan in 1950, where he served as executive director of the Korean Kongsoodo Association. In 1953, Ro re-established the Songmookwan again in Seoul.

True to its Shotokan karate roots, Songmookwan training emphasized basics, forms, makiwara training, and traditional sparring (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 1, Section 5).

Yunmookwan

During Japanese occupation, the Japanese government allowed Koreans to practice judo and kendo. Consequently, in 1931, Lee Kyung-suk (dates unknown) founded a judo school called the Chosun Yunmookwan (Losik, 2001). During the 1940s, Lee hired Chun Sang-sup (dates unknown) to teach judo and kongsoodo. Chun had gone to school in Japan, and there he studied judo during high school and karate during college. With whom Chun studied is not clear, but what he taught and whom he hired as instructors suggest Toyama.

After Korean independence, Chun assumed leadership of the kwan, reopening it March 3, 1946. He named it the Yunmookwan Kongsoodo Bu (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 1, Section 2).

From 1946-1949, the Yunmookwan and the Chungdohwe were the predominant Korean karate schools (Hwang, 1995: 26). As Yunmookwan membership grew, Chun hired Yun Byung-in and eventually Yun Kwei-byung as senior instructors (Lee, 2002b; Lee Se, 2002; Losik, 2001). Both of these individuals had studied under Toyama and had distinguished themselves in Japan.

Chun disappeared during the Korean War. Reports vary from his abduction to his volunteering for a mission into North Korea (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 1, Section 2; Park, 1989: 4).

In 1950, Yun Kwei-byung assumed leadership of the kwan, and renamed it the Jidokwan.[4] After returning to Seoul from the Korean War in 1953, another Yunmookwan student, Lee Kyo-yun, taught tangsoodo in several locations, eventually establishing the Hanmookwan in 1956 (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 1, Section 8).

YMCA Kwonbup Bu

Yun Byung-in (1919-?) was raised for eight years in Manchuria (Kim, 2001), where he studied quanfa (Chinese: fist art; Korean: kwonbup; Japanese: kenpo). He also reportedly studied quanfa in Shanghai (Kim, 2001), which had a large martial arts community during the 1920s and 1930s.

Neither Yun nor his students have specified his Chinese instructor(s) or style(s). However, based on Yun’s legacy, his training appears tohave included changquan (long fist) and Yang taijiquan, two styles that were taught liberally to non-Chinese during the early 20th century (Hsu, 1988; Harvey Kurland, personal communication, March 21, 2000).

In 1937, Yun enrolled at Nihon University in Tokyo, where Toyama reportedly taught karate to Yun in exchange for quanfa lessons. Toyama later included taijiquan in his curriculum for advanced students (International Shudokan Karate Association, 2001). Yun became captain of Nihon University’s karate team and was awarded fourth or fifth dan (depending on the source) and a master’s certificate by Toyama (George Anderson, personal communication, September 18, 2001; Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 1, Section 4). According to Choi Hong-hi, Yun also taught karate and quanfa on a Tokyo YMCA rooftop (Kim, 2001).

Yun returned to Korea in 1945. On September 1, 1946, Yun began teaching kongsoodo and kwonbup at Kungsung Agricultural High School (Burdick, 1997/1999). Shortly thereafter, he also began teaching at the Yunmookwan and also established his own school, the Kwonbup Bu, at the Jong Ro YMCA in Seoul (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 1, Section 4).

Evidence exists that Yun taught some Chinese forms (Yates, 1991) and that he varied students’ training according to body size (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 1, Section 4). Otherwise, no evidence exists of a curriculum that included Chinese training methods, such as qigong (energy mastering), push hands, sticky hands, and specific conditioning, all of which make the forms applicable. Instead, Yun’s legacy indicates a karate-based curriculum. In addition, Yun’s assistant was Lee Nam-suk (1925-2000), whose primary martial arts experience reportedly consisted of self-study of karate from a Funakoshi text (Dussault and Dussault, 1993).

Like his friend Chun Sang-sup, Yun disappeared during the Korean War. His students Lee Nam-suk and Kim Sun-bae reopened his school after the war in 1953, renaming it the Changmookwan. In 1956, Yun’s students Park Chul-hee and Hong Jung-pyo separated from the Changmookwan and established the Kangdukkwan (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 1, Section 4).

Jidokwan

Yun Kwei-byung (1922-2000) began his karate study while attending high school in Osaka, Japan. His teacher was Shito-ryu founder Mabuni Kenwa. Yun continued karate study under Toyama Kanken while doing undergraduate and graduate studies in veterinary medicine at Nihon University in Tokyo (Takaku Kozi, personal communication, October 12, 2000).

Because of his education, refinement, and karate skill, Yun distinguished himself in Japan. Therefore, although many Koreans studied with Toyama, he is one of just two to have received a master certificate (Takaku Kozi, personal communication, October 12, 2000; George Anderson, personal communication, September 18, 2001). In addition, he was reportedly awarded seventh dan by Toyama (George Anderson, personal communication, September 18, 2001; Losik, 2001).

Considered an innovator in both sparring skills and sparring with protective armor (Nakamura, 2000), Yun soon attracted a sizable following (Nagashima Toshi-ichi, personal communication, November 19, 1999).

In 1940, Yun established the Kanbukan (Korean Martial Arts Institute) in Tokyo. This school, now known as the Renbukai, offered classes in karate and open exchange between different martial arts styles (Marchini and Hansen, 1998). Today, Yun is one of very few Koreans found on Japanese karate lineages, although his name is usually transliterated as “In Gihei” or “Yun Gekka.[5]”

Yun was an active member of the mindan (Korean residents’ association in Japan). Even during World War II, he had a large banner on the Kanbukan that read, “Alliance for the Promotion of Establishing the Republic of Korea” (Jinsoku, 1956).

In 1948, Yun returned to Korea (Nakamura, 2000) to teach animal husbandry at Konkuk University (World Karate Championships, 1970). He also became the Yunmookwan’s chief instructor, as well as founder and coach of the karate teams at both Konkuk and Korea Universities.

Following Chun Sang-sup’s disappearance in 1950, Yun became director of the Yunmookwan, which he renamed the Jidokwan (Wisdom Way Institute) (Losik, 2001). Because of the chaos caused by the Korean War, regular training at all schools was disrupted. Therefore, most kwan, including the Jidokwan, are considered to have been re-established in 1953.

In 1961, the Jidokwan joined Hwang Kee’s Korean Subakdo Association, and, with the Moodukkwan, it brought Korean karate teams to Japan in 1961, 1964, and 1970 for goodwill competitions (Hwang, 1995: 39, 70; World Karate Championships, 1970). However, a split in the Jidokwan occurred in 1967, when senior instructor Lee Chong-woo (born 1928) led a group of Jidokwan members to join the Korean Taekwondo Association (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 1, Section 2).

Moodukkwan

Hwang Kee (1914-2002), founder of the Moodukkwan (Martial Virtue Institute), originally called his art hwasoodo (flower hand art). By his own account, he built this art from three sources: 15 months study of quanfa, self-study of taekyon as a youth, and self-study of books on Okinawan karate (Hwang, 1995: 9-18).

From May 1936 until August 1937, Hwang reported that he studied quanfa with a Chinese instructor named Yang Kuk-jin. This training took place in Chaoyang[6] while Hwang was an employee of the South Manchurian Railway (Hwang, 1995: 12-14). Hwang stated specifically that his training consisted of the northern Shaolin tam tui (springing legs) exercise, the Yang taijiquan form, and exercises for conditioning and basic techniques (Hwang, 1995: 14).

In a 1990 interview, Hwang stated that he studied “the northern Yang style of kung fu” with Yang (Liedke, 1990). As Hwang described Yang as being around 50 years of age in 1936 (Hwang, 1995: 12), his birth date would have been in the 1880s. Therefore, he should be (but isn’t) a recognizable name in Yang lineage (Draeger and Smith, 1969: 35-39; Robert Smith, personal communication, December 31, 1999). Unfortunately, Hwang didn’t provide his instructor’s name in Chinese characters, which would facilitate the verification of his existence and his place in the Yang lineage (Robert Smith, personal communication, December 31, 1999). Consequently, many in Korea’s martial arts community doubted Hwang’s claims of quanfa training, based on lack of evidence (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 1, Section 3). Traditional Moodukkwan curriculum is devoid of Chinese training, with the exception of a changquan (“long fist”) form and a Yang taijiquan form, which are only taught to high-ranking masters (Boliard, 1989).

Hwang further stated that from 1939 to 1945, he studied Okinawan karate books (Hwang, 1995: 16, 18). However, he has not stated specifically that he learned forms from books or which books he studied. Many Moodukkwan forms are nearly identical to, but contain movements that clearly predate, early Shotokan versions (Thomas, 1988). This is true whether comparing the forms shown in Funakoshi’s 1922 and 1935 texts, or watching documentary film of circa 1933 showing Funakoshi at Keio University (Warrener, 2001).[7] Although various early karate books were available to Hwang at this time (Noble, 1996b), few offered adequate descriptions and illustrations, and none displayed what would later become Moodukkwan advanced forms. That the Moodukkwan used Shotokan-based class structure, forms, and training methods reinforces Lee Won-kuk’s claims that Hwang studied at the Chungdohwe (Lee, 1997; Massar and St. Cyrien, 1999). Finally, Hwang was friendly with both Chungdohwe and Yunmookwan instructors (Hwang, 1995: 28), and he may have studied with them.

Some sources (Loke, 2000) have suggested that Hwang studied with the future Renbukai and All-Japan Karate-do Federation president Kondo Koichi (1929-1967). These rumors apparently started because of Hwang’s association with Kondo (Graham Noble, personal communication, September 15, 1998) and his mention of Kondo in his books (Hwang, 1995: 40; Hwang, 1978). However, Kondo’s lifelong associate and Renbukai successor Nagashima Toshi-ichi states that Kondo, who began karate study in 1947, was Yun’s student at the Kanbukan (personal communication, November 19, 1999). Furthermore, Renbukai spokesperson Takaku Koji states that Kondo first met Hwang in 1961 (personal communication, October 12, 2000).

Hwang made two attempts to establish hwasoodo classes at the Ministry of Transportation (his employer), but in both instances his small group of students soon resigned. According to Hwang, this was because Korean students lacked appreciation for Chinese-based arts (Hwang, 1995: 24-26).

If these classes are considered the Moodukkwan’s inception, then it was founded on November 9, 1945. If not, then its inception dates to 1947, when Hwang reformed the Moodukkwan. It was at this time that he also changed the name of his art from hwasoodo to tangsoodo (Hwang, 1995: 26).

Taking advantage of space made available to him at little or no cost by his employer, Hwang established many schools along railroad lines. From the standpoint of expansion, this gave the Moodukkwan an advantage over other kwan (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 1, Section 3). Other kwan accused the Moodukkwan of fostering its growth through overly generous standards of admission, discipline, and promotion (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 2, Section 5). Therefore, despite considerable leadership, a legacy of many notable students, and a reputation for upholding tradition (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 1, Section 3), Hwang often found himself in conflict with the Korean martial arts establishment. Numerous attempts in the 1950s and 1960s to include the Moodukkwan in the taekwondo community were unsuccessful.

In 1960, Hwang formed the Korean Subakdo Association (KSA), which would soon include Yun’s Jidokwan. Because of Yun’s friendship with officials in the All Japan Karate-do Federation (some of whom were his former students), the KSA participated in several tournaments in Japan between 1961 and 1970. By 1965, 70% of Korea’s martial art practitioners were KSA members, the largest portion being the Moodukkwan (Hwang, 1995: 44). However, in March 1965, a majority of Moodukkwan students, led by Kim Young-taek and Hong Chong-soo, seceded from Hwang’s organization to join the newly formed Korean Taekwondo Association.

*

Before the Korean War, ROK’s five major karate organizations were the Chungdohwe, Moodukkwan, Yunmookwan, Kwonbup Bu, and Songmookwan. The organizational leaders made many attempts to develop standards and unity, and generally, good relations existed between kwan. Four of the five leaders had studied karate in Japan and all taught curriculums that were karate-based. At that time, Japanese training was respected within the Korean martial arts community; consequently, there was no need or desire to conceal it (Capener and Perez, 1998).

During the Korean War, many Koreans fled from Seoul to Pusan. During this period, kwan leaders maintained communications by establishing the Korean Kongsoodo Association. Its first president, Jo Young-joo (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 2, Section 2), had been president of the mindan in Japan (Jisoku, 1956), and was himself a practitioner of judo (Burdick, 1997/1999).

After the Korean War, there was a period of disunity among the kwan. This started with the withdrawal of Hwang Kee and the new Chungdokwan director, Son Duk-sung, from the Korean Kongsoodo Association. Hwang immediately attempted to form the Korean Tangsoodo Association and join the Korean Amateur Athletic Association.

GENERAL CHOI, THE OHDOKWAN, AND THE INCEPTION OF TAEKWONDO

In 1950, before leaving for Japan, Lee Won-kuk appointed a military officer named Choi Hong-hi (1918-2002) as honorary leader of the Chungdokwan; Choi in turn appointed Son Duk-sung as acting leader of the Chungdokwan (Kim, 2000). Although Choi’s claims have been contradicted by several Chungdokwan leaders (Cook, 2001; 293; Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 2, Section 3), General Choi asserted that he received first dan in karate while attending high school in Kyoto, and second dan in Shotokan while attending Chuo University, from which he graduated in law in 1943 (Cook, 2001; Capener, 1995). Whatever his karate experience may have been, Choi’s role in taekwondo’s development was considerable.

In 1953, Choi founded the ROK Army’s 29th Division, and assigned Nam Tae-hi and Han Cha-kyo (students of Lee Won-kuk) as senior tangsoodo instructors. Nam had taught tangsoodo at the ROK Army Signal School since 1947.

In September 1954, the 29th Division performed a demonstration of tangsoodo for ROK president Rhee Syngman. After watching with great interest, Rhee expressed his desire for all ROK Army troops to be trained in what he preferred to call taekyon (Kim, 2000). Consequently, in late 1954, a new gymnasium was built for the 29th Division. Choi named this gym the Ohdokwan, and he staffed it with instructors from the Chungdokwan.

In 1955, Choi assembled a committee to decide upon a new name for Korean karate. Through a process of compromise between those preferring taekyon-do (referring to the traditional Korean game) and those preferring tangsoodo or kongsoodo, the term taekwondo (t’aegwondo) was chosen. Choi especially liked the term because it referred to both kicking (tae) and hand (kwon) techniques. Rhee eventually accepted the taekwondo name, and it was first implemented at Ohdokwan and Chungdokwan schools.

In 1959, Choi, the administrative leader of two kwan, invited representatives from four major kwan to his home. According to Choi, “My full purpose for this meeting was to get away from the Korean variations in pronunciation for Japanese karate, ‘kongsoo’ and ‘tangsoo’” (Kim, 2000). Choi eventually persuaded the representatives to accept taekwondo as the name for their arts and to join the Korean Taekwondo Association.

Currently, in an effort to provide an indigenous Korean lineage for taekwondo, many taekwondo histories omit the karate and instead emphasize the influence of the traditional foot-fighting game of taekyon (20 Centuries, 1981: 25-29; WTF, 2002a). However, investigation of taekyon shows this connection to have been fabricated (Capener, 1995; Pedersen, 2001: 606).

The Yi Dynasty’s (1389-1910) Confucian emphasis on intellectual pursuits brought about the neglect of military arts, including subak (hand strike), kwonbup, and t’ang-su, all of which were arts closely modeled on Chinese methods (Della Pia, 1994; Henning, 2000).

By the late 1700s, preference for the kicking art taekyon was replacing subak’s yaet bop (literally, “old skills,” referring to hand techniques) (Capener, 1995; Pederson, 2001: 603). Consequently, despite lack of formalized training, taekyon survived into the 20th century primarily as a kicking contest. According to Song Tok-ki, practitioners included common people and gangsters (Capener, 1995; Pederson, 2001: 604).

After the Korean War, the ROK government under Rhee Syngman sought to associate Korean karate with taekyon, with its sweeps and kicks. This influenced the choice of taekwondo as a name for the new Korean art. However, serious interest in taekyon during taekwondo’s formative years was almost non-existent (Capener, 1995), and its influence on taekwondo’s foundation was negligible (Pederson, 2001: 606).

POLITICS, NATIONALISM, AND THE OLYMPICS

The anti-Japanese sentiment that is so prevalent in modern Korean society is based on the Korean memories of Japanese occupation. Like their counterparts in Formosa and the Ryukyu Islands (other colonies seized by Japan between 1878 and 1895), many Koreans during occupation grew up believing that their destiny was to be second-class Japanese citizens (Ishida, 2000). As Lee Won-kuk said, “I never thought that Korea would win its independence from Japan” (Lee, 1997: 46). Nonetheless, after World War II, Korea was free of Japan, and ROK politicians used anti-Japanese sentiment to foster Korean nationalism. Therefore, in the case of taekwondo, this meant consciously separating taekwondo from its origins in karate (Capener, 1995).

In 1960, a student uprising ignited a political process that resulted in the overthrow of President Rhee and eventually the installation of a military government under General Park Chung-hi on May 16, 1961.

In 1962, General Choi organized a meeting of kwan representatives and the Korean Sports Union. After Choi left the meeting early, the visitors agreed on the Korean Taesoodo Association and elected Choi president. Choi reportedly declined the presidency because he had labored to popularize the name taekwondo (Kim, 2000). However, he accepted the position in 1965 and was then successful in changing the name to the Korean Taekwondo Association.

By 1965, Choi had finished designing all of the Chang-hon forms, which were modeled closely on sequences from Shotokan forms (Thomas, 1988). Although they retained traditional karate movements and techniques, these forms received names based on Korean historical and nationalistic themes (A-KATO Org., 2002; WTF, 2002b).

On March 22, 1966, Choi established the International Taekwondo Federation (ITF) to administer to the growing international taekwondo community (Burdick, 1997/1999). However, others feel that Choi formed the ITF because he had been forced to resign the presidency of the KTA.

On March 20, 1971, President Park proclaimed taekwondo as Korea’s national sport, designating its full name as kukki (national) taekwondo (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 3, Section 3). About the same time (January 23, 1971), Park appointed Kim Un-yong (born 1931) as president of the Korean Taekwondo Association. Kim was at the time an assistant director of both the Korean CIA (KCIA) and the Presidential Protection Force (Jennings, 1996: Chapter 9; Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 3, Section 2).

According to Kim, “I accepted the position of KTA president because the Korean government told me to correct the way taekwondo was at that time” (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 3, Section 2). According to Choi (1981), “Park wanted access to the ITF. He saw it could be a powerful muscle for his dictatorship.” Either way, for refusing to hand over the leadership of the ITF to the KCIA, Choi was threatened with jail, which prompted him to relocate to Canada (Jennings, 1996: Chapter 9).

In February 1971, the Korean Ministry of Education issued a requirement that all taekwondo schools have private school permits, thereby subjecting them to government regulation (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 3, Section 5). With this, recalcitrant kwan leaders could be punished for retaining Japanese karate-based art names and traditions, and for refusing to comply with government standards and policies. Standard punishments included media blacklists, suppression of kwan publications, the inability to renew teaching contracts at educational institutions (particularly military and police academies), problems obtaining passports, threats of imprisonment, and assassination attempts (Hwang, 1995: 45-50; Kim, 2000). This treatment marginalized some of taekwondo’s pioneers, to include Choi Hong-hi (moved to Canada), Son Duk-sung (moved to the USA), Hwang Kee (moved to the USA) and Yun Kwei-byung (whose death in 2000 went virtually unnoticed by the taekwondo community).

In November 1971, the Kukkiwon (the Korean Taekwondo Association’s Central Gymnasium) was established, with Kim Un-yong as director. According to Kim, “The Kukkiwon would be the monumental symbol of a nation. The objective of the Kukkiwon is to promote taekwondo as a means of general exercise for the benefit of public health as well as to spread taekwondo as a symbol of Korea and its traditions” (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 4, Section 2).

The following month, on December 23, 1971, Kim announced that he would popularize taekwondo internationally. Toward this end, he would soon publish an English version of taekwondo materials, to include new history and training concepts suitable for distribution in foreign countries (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 3, Section 3). This history attributed the appearance of taekwondo to ancient tribal communities on the Korean peninsula and claimed that taekwondo was chronicled in the 18th century Muyedobo-tongji (Illustrated Manual of martial arts) (Kukkiwon, 1996: 21, Traditional Taekwondo, 1981).[8]

In 1973, President Park designated the Kukkiwon as the World Taekwondo Headquarters and appointed Kim Un-yong as acting president of the newly organized World Taekwondo Federation (WTF). During the inaugural meeting of the WTF, Kim was empowered to select all of the organization’s officials. He further announced, “We are going to promise that taekwondo must become our national sport, as well as an international sport which represents Korea” (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 3, Section 2).

In 1974, the Korean Taekwondo Association consolidated more than 40 existing kwan into just 10 kwan. Additionally, the new kwan were identified by numbers rather than their traditional names. On August 7, 1978, presidents of the 10 remaining kwan signed a proclamation stating, “Taekwondo will strive hard to unify and will eliminate the different kwan of the past thirty years” (Kang and Yi, 1999: Chapter 5, Section 2). Although perhaps not the primary intention, this served to erase connections to the karate-influenced past.

Meanwhile, Kim Un-yong got taekwondo admitted as an official Olympic sport. This was crucial to the ROK’s emergence as a modern international power and to Korea’s desire to have a uniquely Korean martial art.

Although frequently controversial,[9] Kim at various times presided over the WTF, the Korean Taekwondo Association, the Korean Amateur Sports Association, the Korean Olympic Committee, and the Kukkiwon. In addition, he eventually became an executive board member of the International Olympic Committee (112th IOC; Jennings, 1996: Chapter 9).

Kim lobbied tirelessly to bring the Olympics to Seoul and to get taekwondo included in the Olympics. Through his efforts, taekwondo was an exhibition event in the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, and a regular Olympic sport in the 2000 Sydney Olympics. The value of this to the ROK was that the Korean victories in the taekwondo competition catapulted the ROK into tenth place in overall medal counts, which is an impressive achievement for a country with a population of just 47 million (Best Olympic Games, 2000).

Getting taekwondo into the Olympics meant converting it into a spectator sport. For example, the Olympic scoring system, which awards one point for a kick or strike to the body and two points for a kick to the head, perpetuates a Korean kicking tradition, but more importantly, it makes for an exciting spectator sport. It also distinguishes taekwondo from kickboxing, as in the latter, the fighters often throw the mandated number of kicks in the first moments of the round, and then resort to boxing.

Emphasis on free sparring has led to the adaptation of techniques from boxing, a sport in which Koreans have competed admirably since the late 1920s (Svinth, 2001b). For example, the modern sparring and forms use more upright stances than were seen during taekwondo’s early years. These higher stances allow the mobility needed for point-fighting competitions in which throws and grabs are not allowed. Meanwhile, the rules used during point fighting are similar to those used in amateur boxing. Finally, the interest in free sparring contributed to the development of the foam sparring equipment used today during taekwondo and some karate competition. The Korean American Jhoon Rhee was a pioneer in this area.

A distinctive pullover uniform jacket was introduced in the early 1980s for sport taekwondo. One advantage of the pullover is that it doesn’t gap open during competition, causing lulls while the uniform is fixed.

Such changes have taken Olympic taekwondo far from its roots as a martial art: Today it is a combative sport. According to Kim Un-Yong, “We must continue to develop taekwondo into a sport” (Dohrenwend, 2002). According to Choi Hong-hi, “The WTF… simplified the complicated (traditional) moves into a full-contact sparring event convenient for Olympic bouts and television coverage” (Jennings, 1996: Chapter 9). Either way, despite the technical and philosophical changes that accompanied the emergence of taekwondo as an Olympic sport, the desire to maintain Asian tradition still anchors taekwondo to its foundation in karate. Many taekwondo schools still teach traditional karate forms, and the modern ITF and WTF forms use techniques and sequences borrowed directly from Shotokan karate (Nixdorf, 1993; Thomas, 1988). Characteristics such as basic techniques, forms, uniforms, training methods, and protocol still connect taekwondo to its roots in karate.

CONCLUSION

Taekwondo’s origins in Japanese university karate clubs during the first half of the 20th century is well documented. During and after World War II, Korean students returned home with experience in Shotokan, Shudokan, and Shito-ryu karate. Those who chose to establish karate schools taught their arts as they had learned them in Japan, and they called their arts tangsoodo or kongsoodo, which are Korean pronunciations of karate.

Shortly after the Korean War, the ROK government under Rhee Syngman recognized the value of these arts in promoting physical fitness, and encouraged their dissemination. However, ROK nationalism demanded a uniquely Korean name for the arts, resulting in the term taekwondo. The person most responsible for the adoption of this name was General Choi Hong-hi.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the ROK government was controlled by a series of military dictatorships that viewed taekwondo as a strong tool for Korean nationalism. Because of the administrative efforts of Kim Un-yong, the ROK government had the ability to compel the unification of many schools into one style. Thus, by marginalizing dissent, supporting unification with financial and political incentives, and inventing history and traditions, taekwondo evolved into the Korean national sport and eventually an international Olympic sport. This evolutionary process included creating a revised history of taekwondo that claimed a 2,000-year, indigenous Korean heritage while obscuring the art’s true origins in Japanese karate.

Bibliography

Bishop, Mark. (1989). Okinawan karate. London: A. & C. Black Ltd.

Boliard, Greg A. (1989). Korean martial arts student’s manual. Brandon, FL: World Moo Duk Kwan Tang Soo Do Federation.

Burdick, Dakin. (1999). People and events in taekwondo’s formative years, http://www.indiana.edu/~iutkd/history/tkdhist.html (Original work published 1997)

Brigham Young University. (2002). Treaty of Portsmouth.

http://www.lib.byu/~rhd/wwi/1914m/portsmouth.html (Original work published 1905)

Cho, Sihak Henry. Korean Karate: Free Fighting Techniques. Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle

Publishing. pp. 1.

Choi, Hong-hi. Petition from Choi, Hong-hi to the IOC executive board. September 29, 1981.

Capener, Steven D. (1995, Winter). Problems in the identity and philosophy of t’aegwondo and their historical causes. Korea Journal (Student Forum), http://www.bstkd.com/CAPENER.1.HTM.

Capener, Steven and Herb Perez. (1998, July). State of taekwondo: Historical arguments should be objective. Black Belt, http://www.advanced-taekwondo.net/state_of_taekwondo.htm

Della Pia, John. (1994). Korea’s Mu Yei Do Bo Tong Ji. Journal of Asian Martial Arts 3:2 (pp. 62-69).

Donahue, John J. (1993, Winter). The ritual dimension of karate-d?. Journal of Ritual Studies, 7:1 (pp. 105-124).

Dohrenwend, Robert E. (2002). Informal history of Chung Do Kwan tae kwon do, http://www.sos.mtu.edu/husky/tkdhist.htm

Draeger, Donn and Robert W. Smith. (1969). Asian fighting arts. Tokyo: Kodansha International.

Dussault, James and Sandra Dussault. (1993, October). Lee Nam Suk. Inside Taekwondo (pp. 42-49).

Egami Shigeru. (1980). The heart of karate-do. Tokyo: Kodansha International.

Fujiwara, Ryozo. (2000, October 20). Talking about the history of modern karate with Gima Shinken (Trans. from the Japanese). Baseball Magazine.

Funakoshi Gichin. (1973). Karate-do kyohan. Tokyo: Kodansha International. (Original work published 1935)

Funakoshi Gichin. (1997). To-te jitsu [Karate techniques]. Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: Masters Publication. (Original work published 1922).

Funakoshi Gichin. (1975). Karate-do: My way of life. Tokyo: Kodansha International.

Guttmann, Allen and Lee Thompson. (2001). Japanese sports: A history. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Harries, Meirion and Susie Harries. (1991). Soldiers of the sun: the rise and fall of the Imperial Japanese Army. New York: Random House.

Harris, Sheldon H. (1994). Factories of death: Japanese biological warfare, 1932-45, and the American cover-up. London and New York: Routledge.

Harrison, E. J. (1910) Peace or war east of Baikal? Yokohama: Kelly & Walsh Ltd.

Henning, Stanley E. (2000). Traditional Korean martial arts. Journal of Asian Martial Arts 9:1 (pp. 9-15).

Hoffman, Karen. (2000, February 21). Byung In Yoon: Another story, http://www.kimsookarate.com/pages/yoonstory.html

Hsu, Adam. (1986, October). Long fist: The mother of northern kungfu styles. Black Beltpp 64-67, 129-130.

Hwang Kee. (1995). The history of Moo Duk Kwan. Springfield, NJ: U.S. Tang Soo Do Moo Duk Kwan Federation.

Hwang Kee. (1978). Tang soo do (soo bahk do). Springfield, NJ: U.S. Tang Soo Do Moo Duk Kwan Federation.

Ishide Kakuya. (2000, August 12). I was a Japanese soldier, http://www.gol.com/users/coynerhm/I_was_a_ japanese_soldier.htm

International Shudokan Karate Association. (2002). History of Toyama Kanken, http://www.wkf.org/shudokan.html

Ivan, Dan. (1997, March). Bassai dai (comparing Shotokan and Shito-ryu). Black Belt (pp. 32-38, 170.

Jennings, Andrew. (1996). The new lords of the rings: Power, money and drugs in the modern Olympics. London: Pocket Books; a chapter appears online at http://www.ajennings.8m.com/chapt1.htm

Jennings, Andrew. (2001).Sports, lies & STASI Files–A golden opportunity for the press, http://www.play-the-game.org/articles/jennings/sport_lies_stasi.html

Jinsoku Kakan. (1956). Interview with Gogen Yamaguchi about karate-do. Tokyo Maiyu.

Jones, Francis Clifford. (1949) Manchuria since 1931. London: Oxford University Press.

Kang Won-sik and Lee Kyong-myong. (2001). A modern history of taekwondo (Glenn Uesugi, Trans.) http://www.worldjidokwan.com/history/the_modern_history_of_taekwondo.html (Original work published 1999); for a different translation, see http://www.bstkd.com/ROUGHHISTORY.HTM

Kim He-young. (2000, January). General Choi, Hong Hi: A taekwondo history lesson, Taekwondo Times (pp. 44-58).

Kim Kyong-ji. (1986, August). T’aekwondo: Its brief history. Korea Journal 26:8 (pp. 20-25).

Kim, Richard. (1974). The weaponless warriors. Burbank, CA: Ohara Publications.

Kim Soo. (1998, October). Front kick: The natural way. Taekwondo Times (pp. 90-93).

Ko Woo-young. (n.d.) Taekwondo history cartoon. Seoul: Korea Taekwondo Federation, http://winstonstableford.com/TKDCartoon.htm

Korea and Olympism. (1979, February). Olympic Review, 136 (pp. 99-108), http://www.aafla.org/OlympicInformationCenter/OlympicReview/1979/ore136/ore136u.pdf#xml=http://www.aafla.org/search/highlight.gtf?nth=27&handle=000002ca

Korean Embassy. (2000). Korean history–the independence army. Asian Info.org, http://www.asianinfo.org./asianinfo/korea/history/independence_army.htm

Lee Jeong-kyu. (2002, March 7). Japanese higher education policy in Korea during the colonial period (1910-1945). Educational Policy Analysis Archives 10:14, http://epaa.asu.edu/epaa/v10n14.html

Lee Ki-Baik and Edward W. Wagner. (1984). A new history of Korea. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lee Kang-seok. (1997, March). Grandmaster Won Kuk Lee, founder of Chung Do Kwan (interview). Taekwondo Times (pp. 44-51).

Lee Se-ree. (2002). Lee, Chong Woo: Pioneer of TKD, http://www3.nf.sympatico.ca/cot/chongWOOlee.htm

Lensen, George Alexander. (1974). The damned inheritance: The Soviet Union and the Manchurian crises, 1924-1935. Tallahassee, FL: Diplomatic Press.

Liedke, Bob. (1990, May). Korea’s living legend: Tangsoodo-Moodukwan’s Great Grandmaster Hwang Kee (interview). Taekwondo Times (pp. 38-40.)

Loke, M. K. (2002, August). A style is born: Re Yi Wu Kwan Tang Sou Dao. (See new website:

http://www.tangsoudao.com/history.htm)

Losik, Len. (2001, May). The Jidokwan way of wisdom. Taekwondo Times (pp. 74-78)

Losik, Len. (1999, May). The history and evolution of Song Moo Kwan. Taekwondo Times (pp. 64-67).

Mangan, J. A. and Ha Nam-gil. (1998, August). The knights of Korea: the hwarangdo, militarism, and nationalism. International Journal of History of Sport 15:2 (pp. 77-102).

Mangan, J. A. and Ha Nam-gil. (2001). Confucianism, imperialism, nationalism: Modern sport, ideology, and Korean culture. European Sports History Review 3 (pp. 49-76).

Marchini, Ron and Hansen, Daniel D. (1998). History of Renbukai, http://www.renbukai-usa.co

Massar, Frank and Adrian St. Cyrien. (1999, April). Won Kuk Lee, an interview with the true founder of taekwondo. TKD and Korean Martial Arts (pp. 14-17).

McCarthy, Patrick. (1987). Classical kata of Okinawan karate. Burbank, CA: Ohara Publications.

McCarthy, Patrick and Yuriko McCarthy (Trans. and compiled). (1999). Ancient Okinawan martial arts: koryu uchinadi. Boston: Tuttle Publishing.

McKenna, Mario. (2002). So Nechu. International Ryukyu Karate Research Society (pp. 5-8).

Nagamine, Shoshin. (1976). The essence of Okinawan karate-do (Shorin Ryu). Rutland and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle.

Nakamura, Norio. (2000, May.) The people (interview). Karate-do. (Translated from the Japanese)

Nixdorf, Jimmie. (1993, January). The beginning forms of taekwondo. Black Belt (pp. 30-32, 66)

Noble, Graham. (1996a). History of Shorin-Ryu karate. Dragon Times 12 (pp. 15-17)

Noble, Graham. (1996b). The first karate books. Dragon Times 12. (pp. 27, 36)

Park Yeon-hee, Park Yeon-hwan, and Jon Gerrard. (1989). Taekwondo: the ultimate reference guide to the world’s most popular martial art. New York: Facts on File.

Pederson, Michael. (2001). Taekyon. In Thomas A. Green (Ed.), Martial arts of the world: An encyclopedia (pp. 603-608). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Pieter, Willy. (1994). Notes on the historical development of Korean martial sports: An addendum to Young’s history and development of tae kyon. Journal of Asian Martial Arts 3:1 (pp. 82-89).

Renbukai Karate-do. (2002). The little known martial art, http://www.wdob.net/v3/styles/renbukai.htm

Schumpeter, Elizabeth B. (Ed.). (1940). The industrialization of Japan and Manchuko, 1930-

1940: population, raw materials and industry. New York: MacMillan Company.

Svinth, Joseph R. (2001b). Fighting spirit: An introductory history of Korean boxing, 1926-1945. Journal of Combative Sport, http://ejmas.com/jcs/jcsart_svinth_0801.htm (Rev. ed; original work published 1999)

Svinth, Joseph R. (2001d). Karate pioneer Yabu Kentsu, 1866-1937. Journal of Asian Martial Arts 10:2 (pp. 8-17)

Swift, Joe. (2002). Roots of Shotokan: Funakoshi’s original 15 kata (three parts). Fighting Arts Magazine, http://www.fightingarts.com/content02/roots_shotokan_1.shtml

Taekwondo, an Olympic sport for the year 2000. (1994, November). Olympic Review 323 (pp. 475-477), http://www.aafla.org/OlympicInformationCenter/OlympicReview/1994/ore323/ORE323o.pdf

Thomas, Chris. (1998, October). Did karate’s Funakoshi found taekwondo? Black Belt (pp. 26-30)

Toyama, Kanken. (1959). Karate-do nyumon [The introductory text of karate] Publisher?

Warrener, Don. (2000). Gichin Funakoshi: The original Shotokan karate. [Videotape] (available from Masterline Video Productions, 5 Columbia Dr., Suite #108, Niagara Falls, NY 14305-1275, USA)

Wile, Douglas. Yang Family Secret Transmissions. Brooklyn, NY: Sweet Chi Press, 1983. pp. x-xx).

World Changmookwan. (2002). Brief history of Chang Moo Kwan, http://www.worldchangmookwan.com and http://www.geocities.com/Colosseum/Arena/8129/cmkhistory.html

World Karate Championships-October 1970. (1970). Budo 6 (program).

Yang, Jwing-ming. (1999). Taijiquan-classical Yang style: the complete form and qigong. Boston, MA: YMAA Publication Center.

Yang, Jwing-ming and Jeffrey A. Bolt. (1982). Shaolin long fist kung fu. Hollywood, CA: Unique Publications.

Young, Robert W. (1993). The history and development of tae kyon. Journal of Asian Martial Arts 2:2 (pp. 44-69), http://www.amkorkarate.com/ryoung.htm

Notes

[1]. The author wishes to express his appreciation to George Anderson, Ben Brumback, Dakin Burdick, Shannon Burton, Harry Cook, Robert Dohrenwend, Andrew Jennings, Brian Kennedy, Jim Kuhn, Harvey Kurland, Kurosaka Hiroshi, Moo Yong Lee, Eileen Madis, Ron Marchini, Matsumoto Hiroshi, Patrick McCarthy, Dennis McHenry, Tom Militello, Nagashima Toshi-ichi, Graham Noble, Bruce Sims, Michael Shintaku, Kim Sol, Robert W. Smith, Joseph Svinth, and Takaku Kozi.

[2]. During 1923 and 1924, Funakoshi Gichin conducted karate classes in the kendo dojo of Nakayama Hakudo (1859-1958). Nakayama was the 16th headmaster of Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu (Shimomura branch), and at the time, he was arguably Japan’s best-known living swordsman.

[3]. Early names for karate acknowledged its origins in southern Shaolin quanfa. Examples include Ryukyu kenpo (Okinawan quanfa), toudi (China hand), and karate-jutsu (China hand method) (Funakoshi, 1922/1997; McCarthy and McCarthy, 2001: 22, 27, 69). However, Japanese nationalists objected to students training in a martial art with a foreign name. Therefore, in 1935, Funakoshi changed to ideograms that were still pronounced karate-do (empty hand way), but that alluded to Rinzai Buddhism rather than China (Funakoshi, 1935/1973; Guttmann and Thompson, 2001; 147; McCarthy and McCarthy, 2001: 22, 27; Redmond, 2000). In Korean, the ideograms meaning “China hand way” are pronounced “tangsoodo,” while the ideograms for “empty hand way” are pronounced “kongsoodo.”

[4]. In North America, Jidokwan is sometimes transliterated Chidokwan. This latter romanization was popularized by S. Henry Cho, a student of Yun and a major proponent of the style in the United States (Burdick, 1997/1999; Cho, 1968: 1).

[5] Yun Kwei Byung was usually called Yun Gekka by his Japanese friends and students.(Nakamura, 2000; Marchini and Hansen, 1998; Hwang, 1995: 39-40; Takaku Kozi, personal communication, October 12, 2000)

[6]. Chaoyang is in northeastern China, about 250 miles northeast of Beijing. (The precise location is 41.55o N, 120.42o E.) From 1932 until 1945, it was part of Japanese-controlled Manchukuo, but today it is in China’s Liaoning Province.

[7]. Although Warrener claims this film dates to 1924, Harry Cook (2001: 303), Graham Noble (personal communication, July 2000), and Patrick McCarthy (McCarthy and McCarthy, 2001: 131) state that it is early 1930s. Their evidence includes text in the background that describes the emperor as Showa (1926-1989) rather than Taisho (1912-1926).

[8]. About this text, John Della Pia (1994: 70) writes, “In a book of nearly three hundred pages, only sixteen deal with empty-hand fighting and most of the quoted sources in this section are Chinese. With the exception of Hwang Kee’s modern interpretations… none of the martial arts taught as ‘Korean’ today can show a direct connection to this book.”

[9]. Kim’s tactics reportedly included bribery of international sports officials and fight fixing (Jennings, 1996: Chapter 10; S. Korea’s sports chief, 2002).

NOTES:

[1]. The author wishes to express his appreciation to George Anderson, Ben Brumback, Dakin Burdick, Shannon Burton, Harry Cook, Robert Dohrenwend, Andrew Jennings, Brian Kennedy, Jim Kuhn, Harvey Kurland, Kurosaka Hiroshi, Moo Yong Lee, Eileen Madis, Ron Marchini, Matsumoto Hiroshi, Patrick McCarthy, Dennis McHenry, Tom Militello, Nagashima Toshi-ichi, Graham Noble, Bruce Sims, Michael Shintaku, Kim Sol, Robert W. Smith, Joseph Svinth, and Takaku Kozi.

[1]. During 1923 and 1924, Funakoshi Gichin conducted karate classes in the kendo dojo of Nakayama Hakudo (1859-1958). Nakayama was the 16th headmaster of Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu (Shimomura branch), and at the time, he was arguably Japan’s best-known living swordsman.

[1]. Early names for karate acknowledged its origins in southern Shaolin quanfa. Examples include Ryukyu kenpo (Okinawan quanfa), toudi (China hand), and karate-jutsu (China hand method) (Funakoshi, 1922/1997; McCarthy and McCarthy, 2001: 22, 27, 69). However, Japanese nationalists objected to students training in a martial art with a foreign name. Therefore, in 1935, Funakoshi changed to ideograms that were still pronounced karate-do (empty hand way), but that alluded to Rinzai Buddhism rather than China (Funakoshi, 1935/1973; Guttmann and Thompson, 2001; 147; McCarthy and McCarthy, 2001: 22, 27; Redmond, 2000). In Korean, the ideograms meaning “China hand way” are pronounced “tangsoodo,” while the ideograms for “empty hand way” are pronounced “kongsoodo.”

[1]. In North America, Jidokwan is sometimes transliterated Chidokwan. This latter romanization was popularized by S. Henry Cho, a student of Yun and a major proponent of the style in the United States (Burdick, 1997/1999; Cho, 1968: 1).

[1] Yun Kwei Byung was usually called Yun Gekka by his Japanese friends and students.(Nakamura, 2000; Marchini and Hansen, 1998; Hwang, 1995: 39-40; Takaku Kozi, personal communication, October 12, 2000)

[1]. Chaoyang is in northeastern China, about 250 miles northeast of Beijing. (The precise location is 41.55o N, 120.42o E.) From 1932 until 1945, it was part of Japanese-controlled Manchukuo, but today it is in China’s Liaoning Province.

[1]. Although Warrener claims this film dates to 1924, Harry Cook (2001: 303), Graham Noble (personal communication, July 2000), and Patrick McCarthy (McCarthy and McCarthy, 2001: 131) state that it is early 1930s. Their evidence includes text in the background that describes the emperor as Showa (1926-1989) rather than Taisho (1912-1926).

[1]. About this text, John Della Pia (1994: 70) writes, “In a book of nearly three hundred pages, only sixteen deal with empty-hand fighting and most of the quoted sources in this section are Chinese. With the exception of Hwang Kee’s modern interpretations… none of the martial arts taught as ‘Korean’ today can show a direct connection to this book.”

[1]. Kim’s tactics reportedly included bribery of international sports officials and fight fixing (Jennings, 1996: Chapter 10; S. Korea’s sports chief, 2002).

![]()

2 thoughts on “The Evolution of Taekwondo from Japanese Karate”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

President : Koei Nohara 8th Dan from Japan once visited in kolkata our association “Temple of Martial Arts”

Dear sir,

We would like to visit your organizar end of this month i have send you mail in previous mail(k-nohara@) but no reply we got so in this mail i am sending if you get this mail please response

I am Abdul Qader (Kolkata)India

91 8981171937.please give your whatsaap or mobile number that we can exchange idea and can discuss

Yours truly,

Temple of martial art

Abdul Qader

Sir, I am not sure what you mean, please email directly at info@kidokwan.org thanks